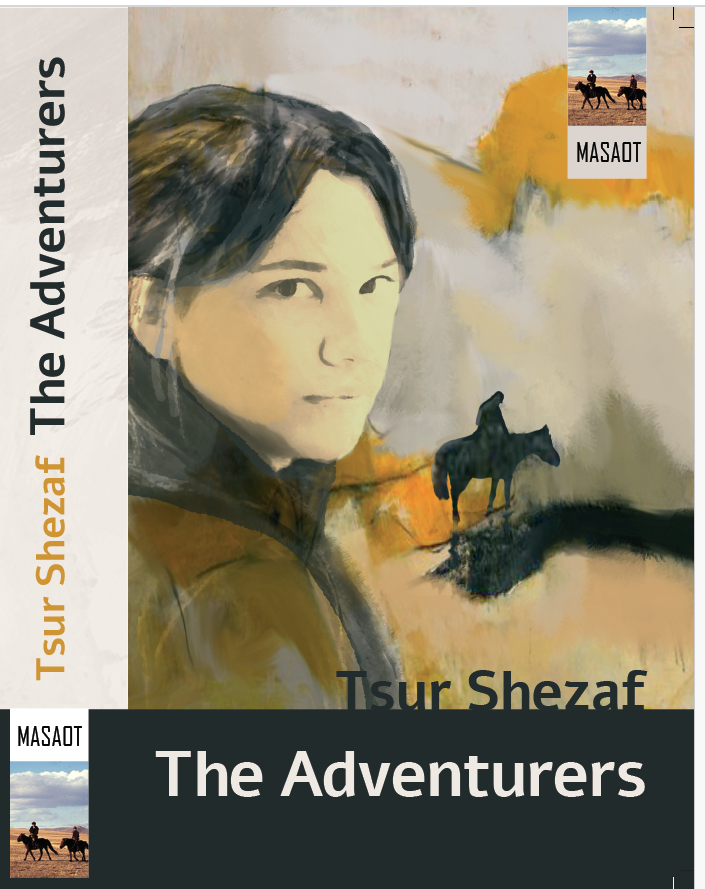

The Advaturers

Original price was: ILS98.00.ILS75.00Current price is: ILS75.00.

Description

On October 24 1917, the first day of the revolution in Odessa, the whites shoot Sarah’s husband, David. The next day, after hastily burying him, Sara flees with Avraham, her seven-year-old son, on the Central Asian roads to Shanghai, leaves the child behind, and returns to trade in the bloody underbelly of the revolution, a young woman for whom nothing stands in her way.

A hundred years later , Aya, her great-granddaughter, joins the man she loves, the leader of a group of warriors abandoned as the world turns upside down. She escapes with him along the trans-Asian roads without knowing that she is following Sarah's journey.

Her love and adventure lead her, a young woman, in a wonderful, crumbling, cruel and dangerous world.

6. Bukhara. Autumn 1920

I gazed at Bukhara’s elegant skyline. The city was bathed in the gold of the setting sun, appearing like a gilded, brown painting. Like the legend it had always been.

Autumn had yellowed the poplar leaves, and large watermelons and yellow, egg-shaped melons, juicy but not too soft, ripened in the fields and were arranged in piles along the road. War or revolution, Reds, Whites, or the Emir’s soldiers—the watermelons and melons, the yellow-green wealth of the Bukhara Emirate, piled up beside the roads, and soldiers would stop and buy from the farmers in exchange for rubles or Bukhara tengas.

I arrived from the west, the setting sun behind me illuminating the minarets, the mighty earthen walls, and the Ark—the fortress palace of the Khan of Bukhara. From where I stood, I could see the walls with their rounded towers, and the sloping wall of the Ark that descended like a massive, steep hill, topped by a small wooden dome. Behind the Ark rose the towers of the Ulug Beg Madrasah like kings’ heads in a chess game. And to the left of the Ark, one could see the rising head of the Kalayan Minaret, earthen brick reliefs adorning its noble neck. It was almost a mile away from me, but I could see it just as I could see the hurrying figures of merchants.

For a moment, I felt tall and elevated above the city I remembered from the first time I arrived there. Even then, still beaten and bewildered and on my way to the unknown, I was struck by the beauty of the golden city, the strength of its people and craftsmen, the hum of its carpet markets, copper wares, precious stones, gold, silk. Everything that made it one of the wonderful cities of the Great Khanate of Bukhara. The most wonderful of them all.

The sounds of the city quieted with the fading day. A moment of stillness at day’s end. A pause in times of turbulence. Of upheaval. From the distance I was from the city, this momentary silence was like a serene breath in days of hurried, frantic breathing. No day resembled the previous day. Even those who sat quietly and tried to live their lives did so in fear of what was to come. Each day harbored disaster or news of victory. And each following day turned everything upside down, revealing that victory had been defeat, and defeat had been victory. The roads were filled with refugees. Near the walls huddled refugees from the Khanate’s villages. The Emirate of Bukhara still held on, but swarms of armies—the Reds from the north and the Whites from the east—approached like dark clouds, casting their shadow across the steppe, devouring people, homes, and livestock in their path.

The armies camped a few kilometers from the city. They had no need to camp closer. Nothing protected the oasis of Bukhara except the desert. And the armies preferred to camp near water sources. From there, they could ride or advance within hours to the walls.

These were grand and terrible days. No one knew what would come. Days of glory or death for the great ones who moved everything and fought over treasures and borders; suffering, hunger, plagues, and firing squads for the little people. For those who knew how to slip away with the shadow and move in the concealment of dust raised by armies, and for those who came after them or fled from them, these were the right days to discover and gather treasures for the days after, when the dust would settle and from it would emerge the contours of the new world. I didn’t know how the next world would look, but I had learned to move slightly ahead of the armies, in that quiet, lawless domain between worlds, in the place where the old world freezes and the new world has not yet been born. In the eye of the storm. It takes time for a new world to be born. And in that time, between worlds, there is space for private worlds. If you have no connection to the old world, even if you were fond of it, you know you should let it go. If there’s anything I’ve learned in the three years during which I’ve crossed Asia from end to end, it’s that even when nothing is the same anymore, on the surface it seems as if nothing has changed. My lips tightened as I thought about what I might find in the besieged city. I could feel the terror and excitement hastening the flow of blood in my body. The twilight silence agitated me, and I let the excitement carry me. I had learned to love the intoxication that fear brings and the anticipation that sharpens my senses, thinking that this is what intoxicates soldiers before a charge. The addiction. This is what the disintegration of the world does, the mighty movement that had engulfed Europe and Asia in tongues of fire, blood, sweat, semen, pain, the cheers of victors and the cries of pain and terror from the vanquished, and the despair of all those caught between the jaws of revolution and the inferno of war.

In the golden light, I suddenly understood that I had become addicted to pain, to passions, and to gambling. The revolution had peeled away what I had been, as if I had removed my house clothes and put on traveling clothes. I had lost my innocence. Until the revolution broke out, I hadn’t known how innocent I was and how fragile and defenseless life is. How weak is the skin. Since then, I had learned to protect it and already knew that the body heals and the soul learns to defend itself. With courage, with fear, with ignorance, with passion, with hopes, and with lies. The war had taught it not to lie to myself. A lie means death. Or rape. Or terrible and miserable abandonment by the roadside. Three years ago, in October 1917, I fled Odessa when the revolution began. A girl-woman of twenty-five with a seven-year-old child. Bukhara was our refuge for the winter months. When summer arrived, we crossed on the Trans-Manchurian line to China and rolled southward to Shanghai. Shanghai was the destination of those seeking refuge from the revolution. On the way from Bukhara to Shanghai, I learned commerce and people. In spring, I left Shanghai back to Asia. By then, I had learned where fugitives hide their money and where those who decided to stay bury it. The time on the roads and in Shanghai taught me what to sell and what to buy. I also knew that nothing—not a person, not a mountain, not a river—would stand in my way. On the first journey, we had rolled ahead of the revolution, swept along with the masses fleeing from it. This time, I turned toward it. Into it. Provoking it. Now I knew what I was doing.

The soil of Central Asia burned beneath my feet. The momentary silence was taut like a golden fabric over a crumbling wall. I had left Tashkent at the last moment. It would be impossible to return to Tashkent, or northward to Astrakhan. From Bukhara, I would continue to Afghanistan, and from there, I would try to return to Chinese Turkestan. And to Shanghai.

Bailey stood beside me, his eyes trying to penetrate the walls. The sun continued its westward descent. I gazed at the golden, misty light.

“You know that if the Cheka catch you, there won’t be much left of you.”

“There’s a certain chance that will happen,” Bailey said. “But as of now, they think I’m John Smith, an Australian prisoner captured by the Turks in Gallipoli who ended up with the German prisoners in Tashkent. If they knew who I was, I wouldn’t be standing here beside you. They sent me here from Tashkent to chase after one Captain Bailey from the Political Office of the Indian Raj.”

“Do you think he’s here?”

“I have no idea,” Bailey said. “I’m Rustam Ali, an Afghan merchant. John Smith, who spies for the Cheka, stayed in Samarkand. And I don’t intend to tell the Cheka who I am until I enter Bukhara from one side, find out what’s happening, and flee like the Buran wind from the other side, not stopping to gallop until I reach the Amu Darya.”

I looked at him sideways and swallowed a smile. I liked him. Disguised as an Afghan merchant with blue eyes, a ginger beard covering his face, tanned from the sharp sun of the high Hindu Kush mountains. But it wasn’t his appearance that appealed to me, but the quiet confidence and patience of a hunter. He was different from the world of merchants, refugees, thieves, revolutionaries, and Russian army officers. One of a kind.

“The Cheka believed you were an Australian prisoner? And who tells you that I’m not from the Cheka?”

“I checked on you. You’re not. You’re a refugee from the Black Sea. They couldn’t tell me if you were Georgian or Caucasian. Though if they had asked me, I would have said you were a White Russian or Ukrainian. Which really raises the question of what you’re doing here dressed like a Bukharan merchant.”

“I am a Bukharan merchant.”

“Tamara?”

“Queen King Tamar,” I smiled.

“Rustaveli?”

“Indeed,” I said. “One day I will gallop with a horse to Jerusalem and search for the place where he was buried beneath the right column of the monastery in the Valley of the Cross.”

“Ah,” said Bailey, “I was actually there with Allenby two years ago, but after that, they sent me back here.”

“To work for the Cheka?”

“Why not? There are so many foreigners there: Germans, Poles, Estonians, Lithuanians, Jews and others, that nothing seems strange, and they are willing to send anyone to try to penetrate the walls of Bukhara. They even equipped me with a letter saying one should help me find that Bailey, an English captain from the Indian Army, who speaks Persian and Tibetan and has been eluding them for a year, inciting the Basmachi here to fight the Red Army and help the Whites. They’re willing to pay quite a bit for intelligence. But I’m an idealist. I do it for the revolution.”

Bailey thought we had met by chance, but I had my eye on him from the moment I heard a bragging Cheka full of Vodka that there was an English spy roaming around. I wanted to touch the Empire. To thank it for the gun. Bailey was my connection.

“An idealist without a doubt. Do you think there’s anything that will stop the Red Army?”

“No,” sighed Bailey. “If I had my Sikhs here, we could manage to stop the Bolsheviks. But no one in Whitehall or Delhi would approve even a company of Gurkhas, let alone a brigade, which is what we need for a start, and a division of the Indian Army, with cannons and everything needed to conquer this part of Asia. We’re too late. If they had slightly bigger balls, it would have been possible to push the Russians away from the Amu Darya, away from Afghanistan and from the mountain passes. The truth is,” he continued to speak, the binoculars stuck to his eyes, “we’re screwed.”

“And what do you want to do?”

“Slip inside. What do you want to do?”

“Slip inside. Can I be your wife for the sake of slipping in?”

“It would be an honor, my lady,” said Bailey. “Why do you want to enter Bukhara just before the Bolsheviks conquer, rape, and plunder?”

“Because I hope to collect treasures and escape with you just before the Bolshevik bayonets.”

“Wonderful idea,” said Bailey, “is the city surrounded?”

“Not from the south,” I looked southward and then westward, “also not from the west. If we reach the market direction, we can enter through the western gate. It faces the Ark, and they say the Khan of Bukhara is waiting for the English and the Afghan Khan, Amanullah, to come to his aid. Maybe he’ll think we’re the expeditionary force.”

“More like Sancho Panza, Don Quixote, and Rocinante.”

“Who is who among them?”

“After you, my educated lady,” said Bailey.

We turned toward the city whose walls were gilded in the last light of the setting sun as if there was no war and as if its last days as a free city, or more correctly as the city of the Khan of Bukhara, weren’t draining like grains in an hourglass.

When we reached the market, it was possible to see that the city was straddling two worlds. Merchants were piling goods onto carts, and the Khan’s soldiers stood guard, ensuring they wouldn’t leave the city. It seemed that many, all those who had something to lose to the Red Army, were about to leave.

We timed our arrival so that the sun would be at our backs and the guards narrowed eyes will be full of direct sun rays, but no one paid us any attention. The gates were open. When I asked one of the merchants how it was that the gates were open, he told me that they were open because anyone who wanted to leave had to pay an enormous sum to escape. The payment was in rubles or afghani. The Khan’s coins weren’t worth much. The Khanate of Bukhara, a Central Asian kingdom centuries old, was about to fall to the Reds.

In the square before the Ark stood the pack animals.

“The Khan isn’t waiting for the Russians,” said Bailey. “If I had a battalion of highlanders, I would wave off these Bolsheviks…”

“You don’t,” I said. “Shall we enter the Ark?”

Bailey looked at me. I felt the excitement climbing up my body, stretching it like a tense spring. Like before jumping from a high place. Not fear, but anticipation of something you have no idea about. My blood flowed faster. I knew my face was flushing and that Bailey could see it.

The fortress walls of Bukhara towered above us. I looked at Bailey, who rode thoughtfully beside me toward the fortress. The last rays illuminated the sloping walls and the Khan’s throne above the fortress entrance.

“Conolly and Stoddart are buried here,” he said.

“Who?”

“Colleagues of mine, who arrived here fifty years ago, and the Khan of Bukhara beheaded them, and the whole British Empire raged that the British Army did not go out to save them.”

“And you?”

“I have no expectations. It’s the profession,” said Bailey.

“Shall we sit here a bit and see what happens?”

We tied the horses in the shade of the tall poplars and sat in a chaikhana opposite the Ark, branchy poplar and mulberry trees shading the wooden benches and tables. And the man from the chaikhana washed the chayniks from old leaves and filled it with boiling water and green tea leaves.

Bailey poured from the chaynik into a piyala, emptied it back into the chaynik, and poured again, repeating the action three times as does anyone born in Central Asia before drinking tea. And then he sighed, said bismillah, and drank the tea. I sipped the hot tea in small gulps.

“The Russians say hot tea is good for lowering body temperature on a hot day.”

“I’ve heard about that,” said Bailey, “perhaps because it equalizes body temperature with the environment, and the body doesn’t need to cool itself and lose water. I studied biology,” he justified when I raised my eyebrow.

“Oxford?”

“King’s College.”

Evening fell. We ate a bowl of wide noodles.

“Lagman,” said Bailey. “It’s from Chinese Turkestan. The Uzbeks and Tajiks brought it from there.”

“How is it there?”

“Beautiful,” said Bailey. “I like it very much. I’m a freak for Central Asia.”

“Look-” I said as several horses emerged from the fortress, accompanied by a guard of several dozen warriors, broke into a gallop, and disappeared into the darkness, their hooves clattering, the echo returning from the houses.

“He’s escaped,” said Bailey.

“Who?”

“The Khan.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course,” said Bailey. “It won’t take the Russians long to realize he’s gone. I’ll need to leave soon too.”

“Shall we go to the palace?”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course.” I smiled, “If the Khan has fled, who will prevent us?”

“Interesting idea,” said Bailey, and his eyes sparkled as he looked at my flushing cheeks. “Let’s go see what’s in the palace.”

“My idea, my findings.”

“If you find them first,” said Bailey. We mounted our horses and rode slowly across the square beneath which Conolly and Stoddart were buried, because the Khan had decided that Victoria was a less important queen than he was, and he had nothing to fear.

The square before the Ark was empty. The gate was closed, but there was a crack in it. Bailey examined the walls.

“No guards.”

“Shall we try?”

We approached the Ark’s gate. Bailey pushed it with his hand, and the gate creaked.

“Outward,” I said, “it’s a gate that opens outward.”

“Where did you learn about fortress gates?”

“How is it in India?”

“Inward,” said Bailey. “Always inward. So that a beam can be placed across. I was right,” he added as the gate yielded to his push.

“Aren’t you going to peek first?”

“If someone is lying in wait, he’ll cut off my nose if I peek. If we enter like kings, no one will stop us.”

“Like kings!” We pushed the fortress gate and entered the long, dimly lit corridor illuminated by torches. The guards had disappeared, and alongside the corridor leading upward on a paved slope were the hatches of the prison, and tortured prisoners stretched out their hands, begging us to help them, to open the cage doors.

“Someone else will open for them,” said Bailey.

We continued upward, to the place where one could see the evening sky at the end of the stone tunnel of the fortress.

There were no guards at the palace gate. We looked at each other. No one prevented us from entering.

We walked slowly but confidently up the paved stone, our shoes echoing. When we emerged into the evening sky, there was a smell of cooking in the air. To our left was the library mosque. We turned right.

“Do you know where the harem is?”

“The harem?” asked Bailey. “I’ve always wanted to visit a harem.”

“Let’s find it.” I stepped forward as if I knew the place. We peeked into the Divani-i-Khas, the throne room where the Khan of Bukhara judged and consulted with his advisors. In the center of the room lay a beheaded body. The head had been severed by a sword blow and rolled not far from it. We approached the body. It was dressed in the palace’s fine clothes. Bailey examined the head and the clothing. He was a high-ranking man.

“He looks like the vizier or one of the ministers.”

“A traitor,” I said.

“He will no longer betray or sell Bukhara to the Russians.”

We turned our backs to the Divani-i-Khas and headed for the harem. The harem women peeked at us in startled fear. The harem guards had abandoned them, and what protected them now was the years-long fear and the tradition that forbade a stranger to reach here lest his head be cut off.

The beheaders had fled.

“He’s on his way to Amanullah, his Afghan cousin,” said Bailey as the women hid from us.

When we entered the Khan’s private quarters, I felt the excitement and the passion and the danger, and something I could not resist made me look at him and say: “Will you sleep with me here?”

Bailey looked at me. The smell of danger, fear, abandonment, and all the treasures of the palace and the women and concubines around us.

“You have no god, huh?”

“And you?”

“I’m English,” said Bailey, “it was never almighty with us.”

He approached me, and we bumped and crashed into everything that was between us and fell on each other on the Khan’s bed, knowing and immediately forgetting that the women and eunuchs were watching us.

When he turned me and put me on all fours and pulled up my dress, I felt his hand on my buttocks and his other hand grasped my hair. And I liked it. My eyes were open. I looked at one of the harem women who was watching us, and her eyes were terror and distress and not-knowing. I had never slept in the light. And certainly not before people’s eyes. My nostrils filled with his scent. For a moment, I thought about how many days I hadn’t bathed and about the days he—I didn’t care. Like him.

I felt the climax approaching, quick, sharp, and sudden. All the fears, all the excitement, all the tension, all that was and all that would be, and then another and another, and then I felt him cumming inside me, and I didn’t care, also because I knew that my period should start soon, and there was no chance I would conceive. We continued to pant as he detached from me, and I remained for another moment on the bed. He lowered the hem of my dress back down. It took me a few more minutes to breathe normally, and then I got up and stood in front of him by the bed.

“I think we should go.”

“Where? This is the safest place in the city.” I liked him.

“I think I should leave the city before the Reds come. Great Britain is on the side of the Whites.”

“And who will tell them that you are you?”

“How many ginger English spies do you know?”

“One,” I smiled. “Will you sleep with me here tonight and leave before dawn?”

“And you?”

“I’ll wait here for the Reds. I have something to offer them.”

“Good,” said Bailey, “a few hours of sleep won’t hurt me.”

“I’m hungry,” I said.

“You have no boundaries?”

“No. And you?”

“Not really,” said Bailey.

“Hey!” I called to the concubine who was watching us, “bring us food and drink.”

The concubine’s eyes were wide open, and her mouth was hanging. She didn’t move.

“You don’t speak Russian?”

“Food and drink please. Now,” said Bailey in Persian.

The concubine nodded and disappeared, returning shortly with a pot of pilaf, pomegranate juice, shorpa, tomato and coriander salad with delicate carrot twirls and lemon on top.

She set the food on a low table. We sat on the Turkmen carpets and ate.

“Where are the guards?”

“They ran away,” said the concubine in Russian. “The Russians will come tomorrow.”

“And do you know what they’ll do to you if you don’t behave nicely?” I looked into her eyes.

“Yes,” said the concubine and prostrated herself before me. “Save me!”

“What’s your name?”

“Masouda.”

“I will save you, Masouda, and all the women of the harem, but it will cost you.”

“I will pay, and I will tell the women. The Khan escaped without us. And the Russians!”

“The muzhiks,” I said, “not good. Stay in the harem and don’t go out. And I will protect you.”

Bailey looked at me from the side, listening. “Yes? How?”

“I have an idea,” I said. “And now watch that no one enters and disturbs us, and wake us an hour before dawn, when the darkness is deepest.”

The concubine nodded, and I started to undress. Bailey looked at me.

“What’s with you, ginger Englishman, have you never seen a woman undressing?”

“Not in the Khan’s harem,” Bailey sighed. “Not such a beautiful one. Like this? As I am?”

“Do you want to shower?”

“I think we both should shower. I don’t know about you, but my chance to shower is not great until India.”

“If you reach India.”

“Thank you,” said Bailey.

“We want to bathe,” I said to Masouda when she returned with another woman.

Masouda nodded. And after a few minutes returned with two more women who brought buckets of hot water and soaps, filling the bath behind the papier-mâché screen painted with designs that had come from India to the harem of the Bukharan Khan.

I plunged into the bath on which rose petals floated, and the women washed and scrubbed me and added buckets of hot water that black eunuchs carried from the clay ovens of the kitchen. And after I got out and the women dried my body, Bailey undressed and entered the hot water with a sigh, and the women scrubbed his back and washed his head and combed his mustache and untangled the knots in his beard, and when he came out, they prepared for him traveling clothes of an officer in the defeated and lost army of the Khan.

Suddenly the skies outside the palace were illuminated.

“What’s that?” I looked at Masouda.

“The Khan ordered all the mosques and madrasahs of the city to be lit.”

“Clever,” said Bailey, “so they’ll think he’s still here. Come,” he said and led me to the window. From the window, one could see the Kalan Minaret, high above the Miri-Arab Madrasah and above the Kalan Mosque. He embraced me, and I listened to his voice in my ear, his beard on my cheek. “The minaret’s bricks were made of clay and straw mixed with milk and egg whites to strengthen them, and they were painted with egg yolk on the outside to make them gleam.”

We stood in silence and looked at the city, a golden halo of torches illuminating its domes and the tops of the minarets. The Kalan Minaret, like a white king in a chess game, towered above the beautiful city, and I thought to myself that even if this were the last sight I would see, I wouldn’t mind.

“Dawn will break soon,” said Bailey as Masouda placed before us a chaynik of green tea and poured and returned and poured again.

“Go on your way,” I said, “I have a conversation with the Cheka.”

“I’ll avoid that conversation,” said Bailey. He turned to the corner of the room where there was a tray with a black-brown lump and sniffed it. “I knew there would be something like this here.”

“What did you find?”

“Ganjah,” said Bailey, “from the Ferghana Valley.”

I looked at him questioningly.

“Hashish. Food of the gods. The nectar they breathe. Something good for long, lonely nights, and also for nights of physical and intellectual pleasures.” He carefully wrapped the lump of ganjah and hid it in an inner pocket of the beautiful karakul coat of the defeated officer. “Take me to the stable and give me a good horse,” he said to the eunuch.

“Goodbye,” I said. “Oq yo’l.”

“Oq yo’l,” said Bailey and winked, disappearing beyond the door, the black eunuch stepping before him.

“Call all the women and concubines and tell them to come to a hall where there’s room for all of them, and tell them to bring with them everything they need for the time they are taken away and to sew a small, hidden treasure for when the Russians arrive, and in this chest, I tapped on the open chest by the bed, they will come and put everything they think I shall need to save you from the Russian soldiers.”

Masouda nodded.

She returned after a short while with a full box. I looked inside. The treasures of the Khan of Bukhara were in the box. I instructed her to pour the contents onto a white muslin cloth and sorted through the jewelry. I knew what I was looking for. Babayoff had explained to me what was the most wonderful thing in the Khan’s jewelry. It could be that he had fled with it, but I had a feeling it was still here. I walked around the room and placed my hand on the drawer chest next to the mirror. I knew it was there. And suddenly I knew why the vizier’s head had been cut off. He stole the stone. Or someone stole the stone, and they both planned to escape with it to the ends of the earth. I opened the drawers and looked inside. It wasn’t there. I looked at Masouda’s face and saw the crease of worry. The tension in the corners of her eyes. The journey had turned my eyes into readers of warning signs, fear, or threat in people’s faces. I was right.

“Where is the stone?”

Masouda looked at me questioningly.

“You know what I’m looking for, and I know it’s with you. It’s either that, or torture and your lives, you choose.” I knew that Masouda knew. I knew.

She approached me and stood on the other side of the drawer chest where my hand was resting. She extended her hand to a cashmere scarf that was carelessly placed on the chest and lifted it. Underneath was a plain white bag. She handed me the bag, and I opened it and took out the largest and most wonderful diamond I had seen in my life. Darya-i-noor—Ocean of Light, the polished brother with countless shades and hues of light of the Koh-i-noor, Mountain of Light, which had been mined in Golconda in India and reached Queen Victoria’s crown, was in my hand. In one unexpected moment, I had become a very wealthy woman. Between me and Shanghai were the highest mountains in the world, wild lands, a revolution, and enormous rivers. I did not intend to lose my head like the vizier who lay in the Divani-i-Khas. He hadn’t surrendered Bukhara to the Russians. He had conspired with Masouda to steal the stone. And she didn’t intend to lose her head because of it.

I sat by the low table and poured more Zhiloni chai, whose green leaves grew on the slopes of the Himalayas. I drank the tea, and without needing to climb the wall and look southward, I knew that Bailey was riding south with all his might. I looked at the diamond and wondered if it’s possible to plan and choose the path even if you know where you are and what goal you want to reach. All is foreseen, yet freedom of choice is granted.